In brief

- A lot of dispute regarding the Treaty comes from disagreement over certain words and concepts.

- Today’s Treaty debate really began in the 1970s.

- If the Treaty gave special privileges based on ethnicity, would it even survive the modern era of one person, one vote?

- Is it realistic to proclaim new rights this far down the road?

We’re words apart…

The Treaty of Waitangi of 1840 has two versions. One written in English and one written in Māori. Considerable dispute has risen over different translations of key concepts between the two documents. Namely, Article 1 refers to Kāwanatanga (sovereignty) of the Crown while Article 2 refers to Tino Rangatiratanga (chieftainship) held by Māori. With the third Article granting citizenship and protection of the Queen.

Put simply, some argue Māori chieftainship trumps the Crown’s sovereignty giving Māori rights to self determination. A view that was backed up by The Waitangi Tribunal, established in 1975, which controversially determined in 2014 that the over 500 Māori signatories never ceded sovereignty to the Crown. Naturally, critics of this view argue there’s ample evidence to suggest the contrary.

Furthermore, the concept of “partnership”, which doesn’t appear in either version of the Treaty, emerged from the 1987 Lands case. The judge in that case characterised Treaty relations as “akin to a partnership”.

The “partnership” concept over management and ownership of resources and assets has since underpinned the “co-governance” concept, which has become politicised, especially in relation to health, water, and local government.

Critics of co-governance say the usurping of democratic accountability in favour of appointed iwi representation is nothing short of revolutionary.

Recent history or distant past?

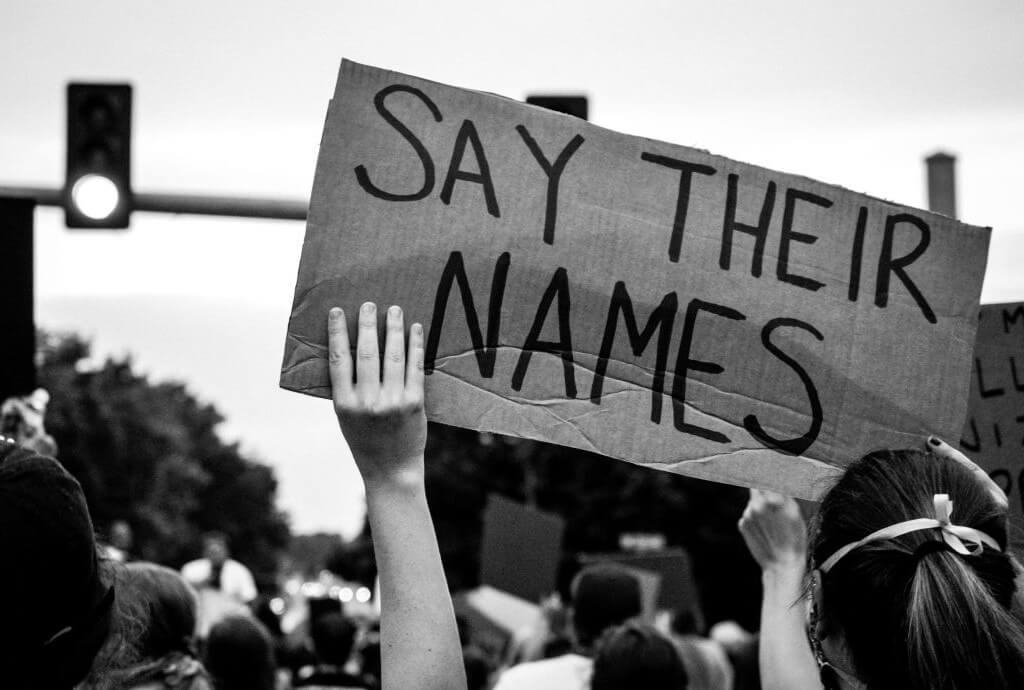

Mainstream historians agree that the modern dispute over the Treaty and its meaning erupted in the 1970s. At the time, many young Māori were becoming urbanised, well educated and influenced by rights movements taking place overseas.

Events like the Land March led by Whina Cooper and the passing of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 brought the debate front and centre to non-Māori New Zealanders.

Some think the relatively recent emphasis on the Treaty has sowed division. Others argue it was because the Treaty was ignored that division occurred.

On the one hand, ACT leader David Seymour says the high expectations of Māori regarding co-governance can’t be met. “For the last 30 years that troika of court, tribunal and public service has been cultivating irreconcilable expectations.”

On the other hand, Associate Law Professor Dr Claire Charters writes “This formalistic view of equality (one law for all), without respect for difference, fails to recognise that treating all people the same under the law can de facto aggravate rather than remedy inequalities”.

Dr Charters doesn’t explain how inequality can be remedied by treatments that by definition seek to exacerbate differences between groups.

A lot has changed since the 1800s

Proponents of Māori self determination like Dr Charters, who was a lead author of the controversial He Puapua report, need to articulate how that ultimately works in 21st century New Zealand. With almost two centuries of immigration and economic development, New Zealand is a multicultural nation that’s come a long way down the road. The feasibility of separating who owns and controls what, based on ethnicity, is contentious and unprecedented.

Ultimately, regardless of interpretations of the Treaty, voters are in the driver’s seat.